Nazi Germany stands out as one of history's largest moral failings, but Americans have our own black mark. During World War II while Jews were being exterminated in Nazi death camps, Japanese-Americans were rounded up and brought to detention camps around the US. While certainly not death camps, these American citizens were taken from their homes and forced to live in miserable conditions for duration of the war. Was it justified?

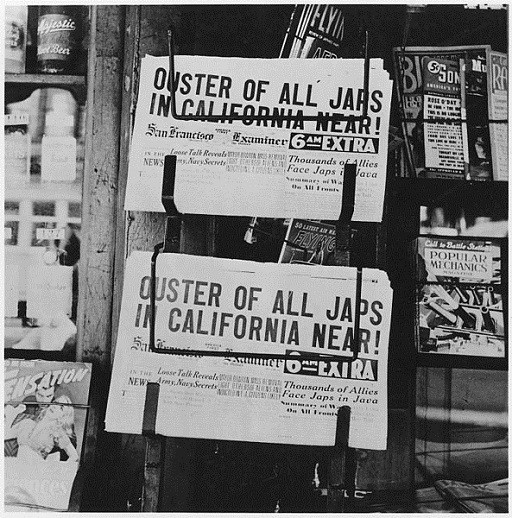

On February 19, 1942, just two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 which authorized the rounding up of anyone of Japanese ancestry and relocating them to the camps. The justification was that Japanese-Americans on the Pacific coast could make radio transmissions to Japanese ships on the Pacific.

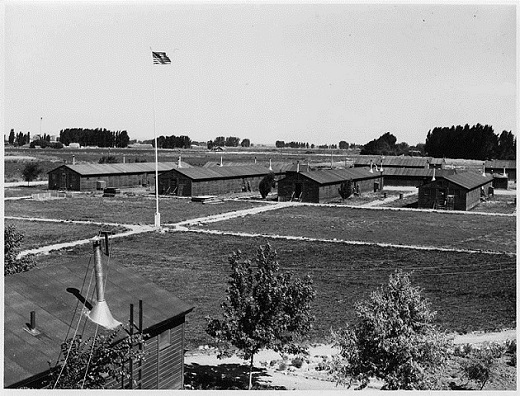

There can be no comparison between the Nazi death camps and the Japanese internment camps. The Nazi camps were killing and torturing factories, aimed at treating other human beings as sub-human, eventually slaughtering them. The internment camps weren't as bad as the Nazi death camps, but conditions were difficult. There was not adequate food or medical supplies, and some Japanese died because of the inadequate conditions. 62% of the Japanese relocated were American citizens. These were not prisoners of war.

You'd think there would be something in the constitution or the bill of rights that would prevent the government from forcibly relocating people because of the race. However, in 1944 the Supreme Court case Korematsu v. United States the Hugo Black court upheld the government's right to relocate Japanese Americans. The court essentially said the danger from potential espionage allows the government to suspend basic human rights for its citizens.

The war ended and eventually Japanese-Americans were released from the camps in 1946. However, they had to rebuild their lives from scratch. Many lost their homes, business, property, and savings. Japanese were not allowed to become citizens again until 1952. Furthermore, Japanese-Americans were subject to some of the worst hatred and racism in the years after the war. It took many years after the war for Japanese-Americans to be fully accepted back into American society.

How deep was the racism and hatred towards Japanese-Americans during the war? Even children's book author Dr. Seuss got into the act. The same author that created One Fish Two Fish and The Can in the Hat dutifully cranked out numerous cartoons depicting Japanese as the enemy. You can see examples in the links section. After the war, Dr. Seuss wrote Horton Hears a Who! partly as an apology to the Japanese-Americans he'd demonized during the war.

In a bit of collective remorsefulness, in the Civil Rights Act of 1988, America essentially apologized to the Japanese-Americans interned in WWII and their descendants. Some of the text of the act is

The Congress recognizes that, as described in the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, a grave injustice was done to both citizens and permanent residents of Japanese ancestry by the evacuation, relocation, and internment of civilians during World War II.

As the Commission documents, these actions were carried out without adequate security reasons and without any acts of espionage or sabotage documented by the Commission, and were motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.

SUBMIT A COMMENT