Cambodia is a small country in Southeast Asia that in the 1970s became the site of one of history's worst genocides. The brutal regime of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge killed over 2 million people, or around one quarter of the population of Cambodia. How was this allowed to happen? Did the rest of the world not know what was going on, or was the world indifferent?

Cambodia gained its independence from France in 1953. From 1953 to 1970 Cambodia was ruled by the monarch Prince Sihanouk. Cambodia is located right next to Viet Nam but had remained neutral in the Viet Nam War during the 1960s. In 1970, Prince Sihanouk was overthrown by a right-wing force backed by the US led by lieutenant-general Lon Nol. A small guerrilla force called the Khmer Rouge had been founded in 1960 and was led by Pol Pot, a follower of Chinese style Communism. After 1970, the Khmer Rouge joined forces with Prince Sihanouk to attack Lon Nol's forces and gain territory within Cambodia, and thus began a civil war. As the war in Viet Nam persisted, US bombers dropped untold tons of napalm and cluster bombs on the Cambodian population in its attempts to destroy the hideouts of the North Vietnamese. Many civilians were killed by the bombardment, and since Lon Nol's government was allied with the US, many civilians were convinced to be recruited by the Khmer Rouge.

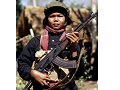

On April 17, 1975, the capital city of Phnom Penh fell to the rebels and thus began rule of the Khmer Rouge. Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge set out to create the "ideal" communist model of a society, which all Cambodians would work as laborers in a huge collective farm. The idea was to deconstruct the society and return Cambodia to a pure agricultural "Year Zero" where all modern western influence was removed. To achieve this, the regime forced all Cambodians to move from their homes into agricultural labor camps, and they sought to "eliminate" all of the unwanted or incapable members. Anyone who refused to move from their home was killed. Anyone who expressed opposition to the regime was killed. Factories, schools, and hospitals that were privately owned were all shut down and the owners were killed. Children were separated from their parents. Any kind of religion was banned. Laborers in the fields were forced to subsist on a teaspoon of rice per day, so sickness and malnutrition were rampant. Those too weak to keep up with the forced labor were killed. Khmer Rouge officers wore distinctive red scarves as they patrolled the fields with their rifles. They could shoot anyone at any time for smiling, crying, or speaking a foreign language. The fields of Cambodia bore strong resemblance to the notorious Nazi death camps of World War II.

Estimates are that 2 million people were killed between 1975 and 1978 by the Khmer Rouge regime, which was somewhere around 1/3 of the population. Foreigners had been expelled from the country so no one knew what was going on. French priest Father Francois Ponchaud had begun doing missionary work in Cambodia in 1965. He was one of the last foreigners expelled, but by September, 1975 Ponchaud had become a liaison for refugees who made it over the Thai border and wanted to tell the story. His accounts from the refugees appeared in the French press starting in October, 1975. He also contacted Amnesty International and other human rights organizations to try to get the story out. In 1978 Ponchaud published a startling account of the killing in Cambodia. Still, the world was not interested. Most of the world was unaware, and those who heard the stories could not believe them.

The US, for its part, had finally gotten its troops out of Viet Nam in 1975. While stories of the terrible killing did reach the government, US policy was shaped by its opposition to Viet Nam after 12 years of war, so strategically they were allied with the Khmer Rouge who also opposed its neighbor Viet Nam. President Carter vowed to make human rights part of US foreign policy, but it took many months for Carter to condemn the Khmer Rouge for its abuses, and still there was no help for the Cambodian people. Finally, in December, 1978, Viet Nam overthrew the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia and the world started to see that Ponchaud's stories were true. The US was still in an awkward position as they opposed Viet Nam, and the Khmer Rouge was still allowed a seat in the UN until 1993.

Dith Pran was a Cambodian photojournalist and interpreter who worked with New York Times journalist Sydney Schanberg. His ordeal was made famous in the 1984 movie "The Killing Fields." Prior to the Khmer Rouge taking power, Schanberg and Dith worked together to report the news back to the US. When it was clear the Khmer Rouge would take power, it was arranged for Dith's family to leave Cambodia but Dith stayed to continue working with Schanberg as reports of the impending coup were sent . Unfortunately, Schanberg and the other reporters were unable to prevent Dith from being sent to the fields with the other Cambodian victims. Once back in the US, Schanberg tried valiantly to get any news of what happened to his friend. He was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1976 and dedicated it to Dith Pran. Dith survived the labor camps and somehow escaped and was able to reach the Thai border in October, 1979. Sydney Schanberg flew to Thailand and was overjoyed to be reunited with his good friend. Afterwards, Dith came to American to reunite with his family. He became an American citizen, worked for the New York Times for many years while also speaking frequently about the Cambodian genocide and his experiences.

In the aftermath of the Cambodian genocide, the country is now relatively peaceful. The UN called for a tribunal to try members of the Khmer Rouge in 1994. Pol Pot denied everything and claimed to have a clear conscience until his death in 1998, and in 2007 trials were held for remaining Khmer Rouge members, though many were already gone by this time. As with other genocides, the Cambodian people will never get retribution for the terrible ordeal that caused nearly 1/3 of its population to perish.

SUBMIT A COMMENT