What would you do if you were an athlete and someone offered you more than your yearly salary - to lose? We all would like to believe that if we ever were so lucky to be so talented to have the opportunity to play baseball - a kid's game - and make lots of money doing it, we'd never do anything so unsavory as to commiserate with gamblers and promise to lose for a payoff. Add to this - years ago ballplayers didn't make the same out of proportion salaries that they do today, and there was no free agency. Team owners paid their players what they wanted, and the players had no negotiating power. Eight ballplayers for the Chicago White Sox of 1919 were confronted with an owner they hated and a bunch of gamblers who offered them more money than they'd ever known, if they'd only do them a favor and lose the World Series. Their story is one of the most perplexing moral dilemmas ever.

The 1919 White Sox were unquestionably a great team. They had one of the greatest players of all time in Shoeless Joe Jackson, and two excellent starting pitchers in Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams. As they approached the end of the season, it was clear they'd go to the World Series. The climate around baseball in those days was very mixed up with gamblers. Payoffs were routine in all kinds of professional sports, as there was often more money in losing than winning. However, the World Series was a huge sports spectacle, and no one could imagine players throwing the World Series.

Most of the popular understanding of the events comes from the book "Eight Men Out" written by Eliot Asinof, published in 1963 and later made into a movie. Some of the facts are in dispute as to who's idea was it, who took what money, etc. It is clear that some number of White Sox players held a number of meetings with gamblers, where payoffs were discussed and throwing games in the World Series was discussed. The plan was started by 1st baseman Chick Gandil and professional gambler "Sport" Sullivan, though it's not clear whose idea it was. Gandil demanded $80,000 to recruit players in the fix, money that Sullivan would raise through connections with other shady gamblers. The plan became real when Gandil convinced starting pitcher Eddie Cicotte to go along. Cicotte resisted at first, but he was under considerable financial pressure. His salary was only $6000, and he was 35 years old with a family and he'd just bought a farm. Legend has it Cicotte was offered a $10,000 bonus for winning 30 games, and when he reached 29 wins owner Charles Comiskey had him benched to avoid paying the bonus. Cicotte finally agreed to take part in the fix, on the condition he be paid $10,000 before the first game. Once the agreement was made with Cicotte, there was no turning back. The #1 starting pitcher would have more influence in the outcome of the series than anyone.

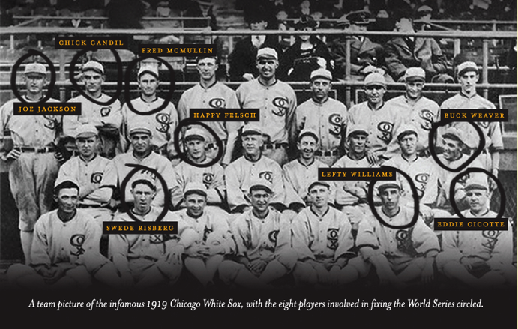

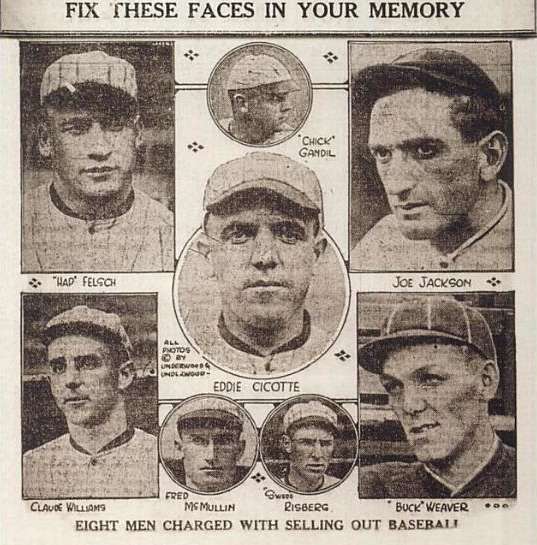

In the lead up to the World Series, a number of other gamblers got involved, and a total of 8 players were recruited to take part. After Gandil and Cicotte:

- Shoeless Joe Jackson - He was the team's best player. He was illiterate and did not participate in the meetings, but did not turn away the money.

- Lefty Williams - He was the team's second starting pitcher, with a great deal of influence on the outcome of the games.

- Swede Risberg - He was the team's shortstop and a willing participant.

- Happy Felsch - He was one of the team's outfielders.

- Fred McMullin - McMullin is an interesting case as he wasn't a starter on the team and he'd have little influence on the games' outcome.

- Buck Weaver - Weaver was the team's starting 3rd baseman. He participated in the meetings, but never agreed to participate and never accepted a payoff.

A number of gamblers were involved once Sullivan began his efforts to raise the money. Sleepy Bill Burns, a former ballplayer, and Billy Maharg, a former boxer, began their own effort to deal with the players and raise money. Arnold Rothstein and his sidekick Abe Attel were approached. Rothstein had the money to finance the whole deal, but thought the idea was too risky. Or did he just want to cover his tracks. It's not clear with all of the shady promises and double-crossing what actually happened. It's not clear which players after Cicotte received what payoff. What is clear is that the White Sox lost 4 of the first 5 games, two each lost by Cicotte and Williams. The 3rd starting pitcher, Dickie Kerr, was not involved and was actually trying. Gamblers were crossed up when the White Sox won games 3 and 6, and Cicotte actually decided to try in game 7 and won that one as well. The series stood at 4 games to 3 in the best of 9 series.

At this point, according to Asinof's account, the gamblers arranged for a hit man to threaten physical harm to the wife of Lefty Williams if he did not dump the 8th game in the first inning. Williams gave up 3 runs right away in the 1st inning and was removed from the game. Cincinnati won game 8 10-5 and with it won the World Series.

The aftermath of the White Sox series loss was an adventure by anyone's account, as rumors of the fix were out in the open. Owner Charles Comiskey offered a $20,000 reward to anyone who would come forward with evidence of the fix. He also stated that a certain 7 players would not be returning to play for his team. Newspaper columnist Hugh Fullerton published a scathing article in December of 1919 presenting his evidence that the series was fixed. He'd kept track of every suspicious play during the series, but at this point there was no smoking gun. Fullerton was criticized from many angles, as officials from baseball did not want to see their sport reduced to a mockery.

The 1920 season commenced, and Comiskey ended up keeping all of the suspected players except Gandil. Eddie Cicotte and Lefty Williams both won more than 20 games, and Joe Jackson and Buck Weaver batted well over .300, even with the suspicions of the World Series fix still in the air. Then in September, 1920 a grand jury was convened to investigate another fix, and the attention returned to the White Sox in 1919. Gambler Billy Maharg was interviewed in a Philadelphia paper and revealed many of the details of the fix. Cicotte, perhaps because of a guilty conscience or perhaps because he saw that the fix would be exposed imminently, decided to confess. He explained that he'd resisted taking part in the fix at first, but he needed the money. Joe Jackson went before the grand jury soon after and confessed as well. It was reported that a kid outside the courtroom said to Jackson "Say it ain't so, Joe" Jackson denied that the exchange ever happened, but it made for a stunning memorable moment in the movie "Eight Men Out." Lefty Williams soon after became the 3rd member to confess.

The story gets really weird as the written confessions from the 3 players magically disappeared from the state attorney's office. Hmm, I wonder how many people were paid off to make that happen. Even weirder was Sport Sullivan and Abe Attell were sent out of the country, so when Arnold Rothstein was brought before the grand jury there was no direct link to the man who undoubtedly financed the entire fix. Indictments were handed down to the eight players and 5 of the gamblers involved, but not to Arnold Rothstein. At the trial, gambler Sleepy Bill Burns was given immunity and he testified for 3 days about the whole sordid affair of payoffs and double crossing that occurred. Burns ended up broke from the deal as he bet on Cincinnati in the 3rd game which the Sox tried to throw but failed. Maharg also testified. Despite all of the evidence presented, the case failed because of the missing confessions and the players were unbelievably acquitted of any wrongdoing. They'd be back on the field again to start the 1921 season.

Not so fast. Newly appointed Commissioner of baseball Kenesaw Mountain Landis declared after the trial:

Regardless of the verdict of juries, no player who throws a ballgame, no player that undertakes or promises to throw a ballgame, no player that sits in conference with a bunch of crooked players and gamblers where the ways and means of throwing a game are discussed and does not promptly tell his club about it, will ever play professional baseball.

None of the players did ever play again. Joe Jackson was one of the greatest players who ever lived, with a lifetime batting average of .356. Jackson loved the game so much that after he was banished, he kept showing in on minor league teams under assumed names, until they discovered him and kicked him out probably because he was so much better than the bush leaguers. He played tremendously in the 1919 series. He couldn't read or write, but I think he knew perfectly well what was going on. Asinof depicts Jackson as totally conflicted, asking his manager not to play in the series. He clearly didn't throw the series, but he took the money.

Buck Weaver is the most interesting case. He refused to take any money and played to win in the World Series. He knew about the fix right from the start and refused to take part, but he didn't go to his manager or any authority. That was his crime. After being banned from the game, he repeatedly applied to the Commissioner to be reinstated, claiming he should not have been included with the players who threw the World Series. He was repeatedly denied and he never played professional baseball again, just like the other 7.

Does Sleepy Bill Burns get any credit for telling the whole truth at the trial? Did he have a sudden moral rehabilitation or was he just resentful that he didn't make the expected fortune putting the fix together. It's hard to see how any of the gamblers acted out of anything but greed.

The 1919 World Series has become known as the Black Sox scandal. This statement by Landis became the guiding principle for baseball and for athletics in general. Since the Landis ruling, baseball has seen players cheat with spitballs, corked bats, and all kinds of notorious drugs. Baseball tolerated some of the ugliest racism. But no one will ever take money to purposely lose. Pete Rose, some 68 years after the Black Sox scandal, was banished for betting on baseball and to this day has not been admitted back and cannot be considered for the Hall of Fame, though he was one of the greatest players of all time.

SUBMIT A COMMENT